From economy to ecology

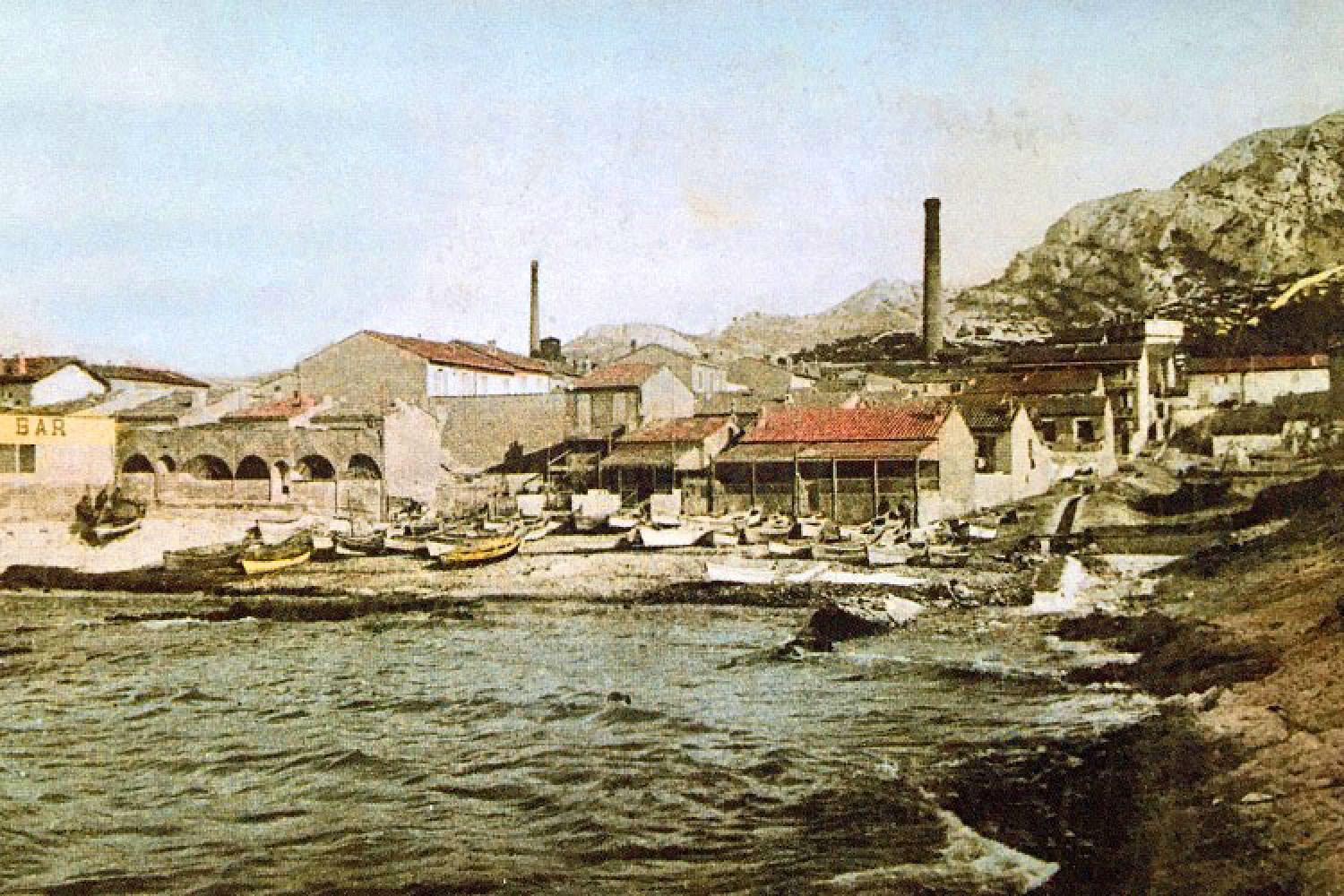

Marseille: an industrial and port location

Since Antiquity, Marseille has been at the centre of commercial exchange in the Mediterranean basin. This privileged position was favourable to the economic development of the city and its port. This industrial-port complex handled various ores from the Mediterranean area, and further afield, thanks in particular to the opening of the Suez Canal.

Marseille's soap factories were the first industry in the 17th century, but it was in the 19th century when Marseille's industry really took off, becoming a major centre of employment and attracting significant immigration.

This considerable development of factories in the centre of the city was eventually interrupted by Napoleon I. The pollution generated became so unbearable for local residents that an imperial decree was signed on 15 October 1810, and in 1825 a Health Council was created in Marseille to relegate industrial activities to the urban fringes.

Factories in the heart of natural spaces

Industries needed to move, but where? Pollution had to be moved away from the city while remaining close to the sea to facilitate the transport of materials. The southern coastline of the city of Marseille had all the necessary characteristics, especially as this sparsely populated coastal strip was beaten by the Mistral wind, which carried the polluted air out to sea.

The first factory was set up in the Calanque de Saména in 1810: it made soda for the soap industry from the limestone rock in Mont Rose. And this was only the beginning! The Calanques area, especially the coastline between Montredon and Callelongue, soon became a favoured site for the chemical and metallurgical industries: lead, soda, sulphur, tartaric acid, sulphuric acid, silver, glass... and oil was even purified at Col de Sormiou!

Further on, at La Barasse, bauxite was extracted, while the banks of the Huveaune saw the arrival of a dense, diverse industry. A blast furnace was constructed on the Bestouan beach at Cassis, while the enormous shipyard of La Ciotat was developed opposite Mugel. And this is without counting the quarries (see inset below) that abound in the area... There were even sand quarries at Riou and in the Calanques de Marseilleveyre and the Calanques de Sormiou ! As a result of this economic growth, the number of workers in the city of Marseille rose from 10,000 in 1834 to 40,000 in 1880.

From the industrial revolution…

Modernity was on the march and the southern coast of the Calanques saw the appearance of rails, access ramps, cable cars, tunnels, wagons, carriages and steam engines! Wharfs were developed, such as at L’Escalette, to accommodate the coasters that brought the ores from the port of Marseille: in fact, the narrowness of the creeks and their shallow draught prevented large tonnages from landing. After the factories had processed the raw materials, these small boats took the finished products to La Joliette, from where they were sent to the four corners of the world...

… to the ecological revolution

But the arrival of factories led to the reduction and impoverishment of the natural spaces. For example, the fine sand that was previously a feature of this coast, especially in the creeks of Montredon, was used for glass-making. With its disappearance, a whole universe of plants and animals has become extinct.

Humans also suffered the impact of this activity. "Cheminées rampantes" (chimneys that climbed up the steep slopes) were installed on the hills at the request of public authorities in order to keep the toxic fumes away from the factory when the mistral wind was not blowing. In fact, various complaints and petitions were lodged by local people, concerned about the decline in their health, and the effect on their pastures and their fields.

Due to international competition, technical developments and economic fluctuations, most of Marseille's industries declined in the 20th century. In addtion, there was a fundamental change in the consciousness of citizens: the Calanques was no longer seen as a hostile environment, but a space of freedom where one could recharge one's batteries and enjoy nature.

The inhabitants mobilised to demand the closure of the factories, some of which moved to the Etang de Berre and Fos-sur-Mer, which today is the largest industrial area in France.

The industrial footprint in the Calanques

Walking through the Calanques today, you will see various traces of this past, whose history continues in other ways: such as at Goudes or Callelongue where the industrial buildings have been converted into homes, at L’Escalette now an open-air art gallery and at La Madrague de Montredon where the Legré-Mante factory is at the heart of a complex redevelopment project.

The problems of pollution and the question of their impact on humans continues, because although the southern Marseille coast has a low population density for a city, it remains the most densely inhabited area of the Calanques National Park and the area most visited by holidaymakers.

Buildings in disrepair, "cheminées rampantes" (still very visible, especially above la Madrague de Montredon and L’Escalette), slag deposited in slag heaps, ecological imbalances: so many remains inherited from a bygone era where nature took second place and seemed so immense that it would be able to withstand all aggressions.

Managing site pollution

Today, ADEME is leading an ambitious programme to reduce the amount of slag present along the southern coastline: the aim is to remove it from the natural environment where possible (asbestos deposits at Les Goudes, for example), or even to contain it and ensure that it no longer contaminates the surrounding natural habitats, such as in some cases in the shoring of the coastal road.

The National Park brings its scientific expertise to this operation to prevent or minimise damage to the natural environment in the choice of technical solutions proposed and in the future implementation of the works. The Astragale de Marseille, replanted by the National Park, as well as the Coronilla juncea, are also used to fix and hold the pollutants.

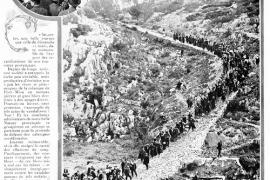

From the early 20th century, inhabitants mobilised against the presence of the factories. The first mass demonstration took place in 1910, next to the Port-Miou quarry, to protest against the destruction of the site's natural beauty.

Xavier Daumalin, lecturer in contemporary history at the University of Aix-Marseille

Quarries in the Calanques

One of the industries that developed in the Calanques and the surrounding hills was the extraction of limestone, a natural resource that is found in abundance in Provence.

The limestone found in Marseille is of an Urgonian type, which means it is a light-coloured, compact, hard and "fossiliferous" (rich in fossils). The famous "Cassis stone" is of this type. This stone is no longer quarried today, but it was previously used to make sinks (the famous Provençale "pile"), pavements, and buildings in the region, as well as, thanks to the export of the port of Marseille, quays in Toulon, Alexandria and the Suez Canal! But the conditions in these quarries were extremely difficult for the hundreds of workers who worked there...

These quarries, exploited since Antiquity, were mainly located on the Port-Miou peninsula and at Pointe Cacau (where the famous silos are located), but also extended as far as Carnoux... and there were even some on the Frioul islands! Still visible today by the shapes of the cuts that have been left behind, they were used for cut stone as well as crushed limestone for making floors, lime... and toothpaste!

At Le Frioul, the cleared land allowed the installation of a lazaretto, and the cliffs created made the forts located at the top inaccessible. The last seaside quarry, closed in the early 2000s, was located at Bestouan in Cassis. Within the Saint-Cyr Massif, the Perasso de Saint-Tronc quarry is the last quarry in operation located near the heart of the Calanques National Park.

Video and sound

Video and sound

The Calanques' industrial heritage on France Bleu

The history of Marseille's industrial past on France Culture

Links

Links

La Barasse Walking tour booklet: industries and landscapes (in French)

The ecological restoration of polluted areas in the Calanques National Park

Virtual visit of industrial remains in the Calanques in the web-documentary En marges

Dive into the industrial past of the Calanques

Stone extraction in the Saint-Cyr range

Marseille and its industrial past, a history in the journal: La Marseillaise

The deindustrialisation of Marseille: interview with Xavier Daumalin

Reading

Reading